Lutherie Books in General

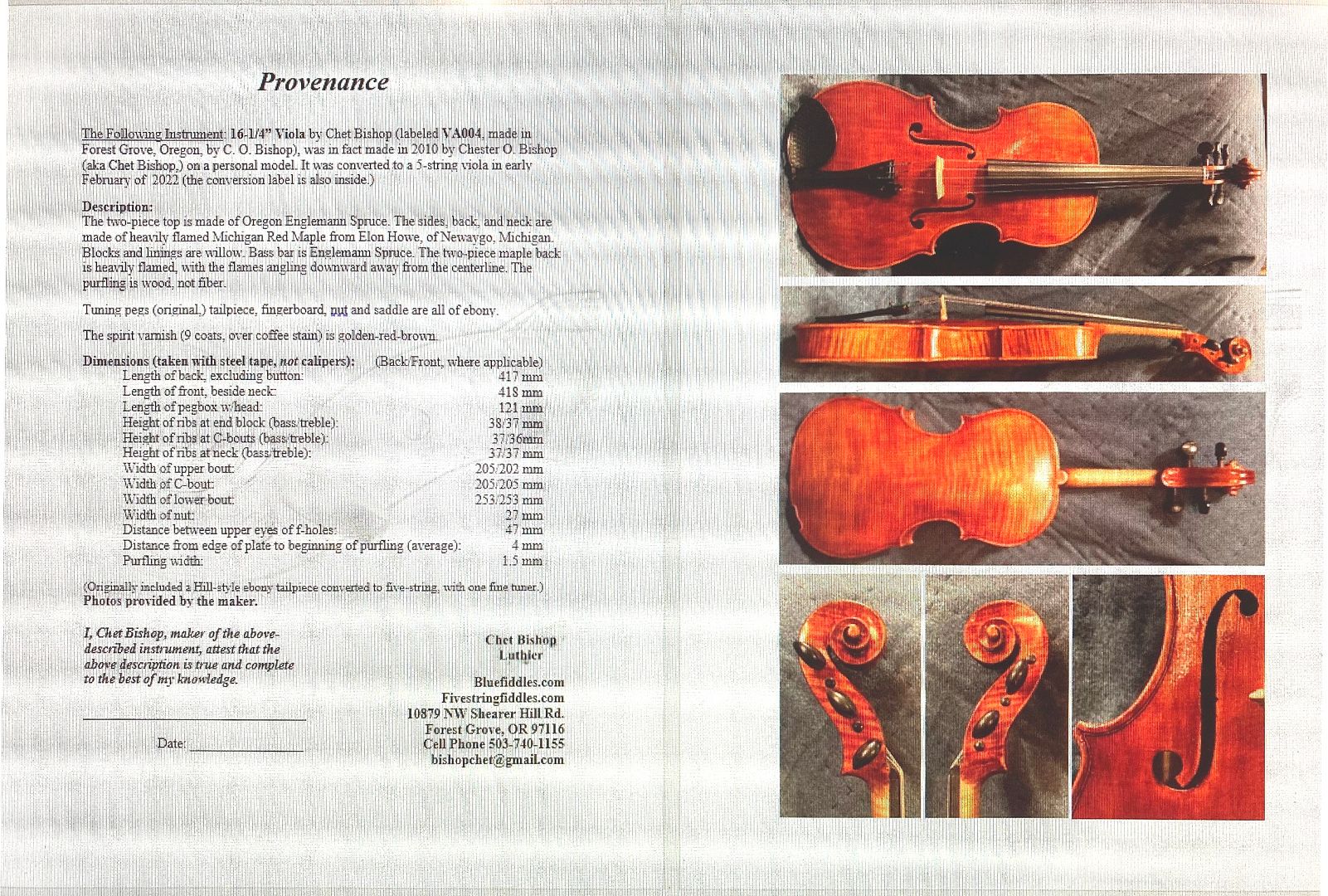

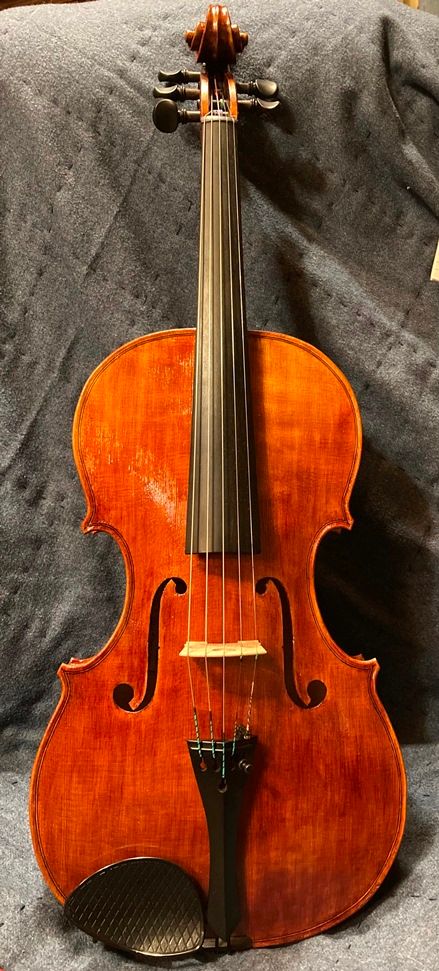

This is the beginning of my “offerings” to the reading public, regarding the building of Violin-Family instruments. I currently build Violins, Violas, Cellos, and Double Basses, as well as the Five String Variants of each.

The instruments have been making customers happy wherever they go, but I have come to realize that I will only be able to build so many instruments before my body will no longer cooperate. So I am attempting to take some of the things I have learned and experienced, and make them available for others to use and enjoy. (The headings below are links to the Amazon sites where the books are available.)

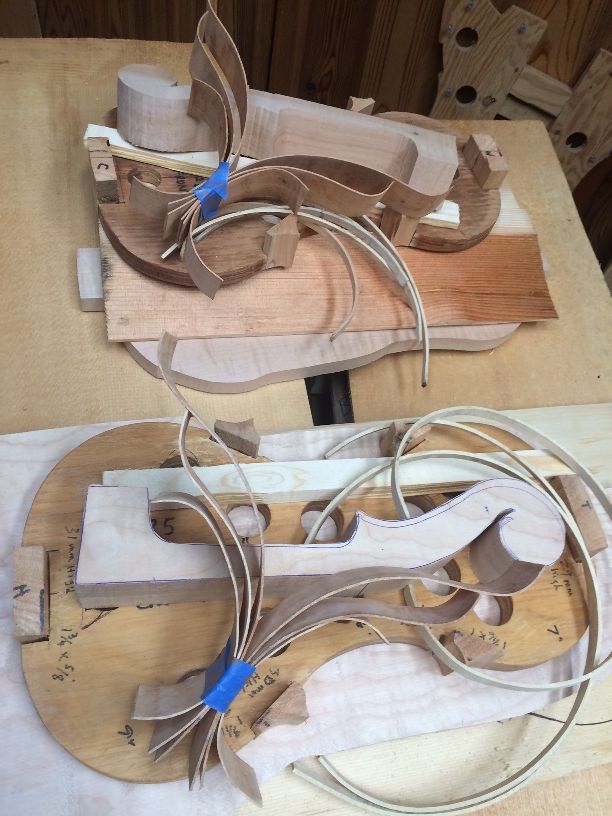

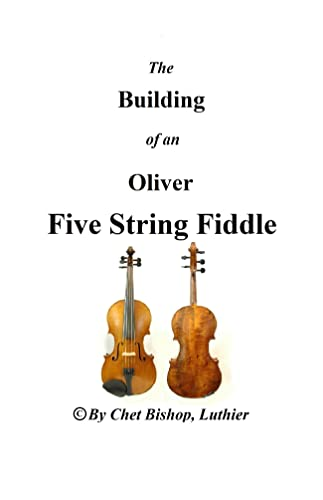

Building an Oliver Five String Fiddle

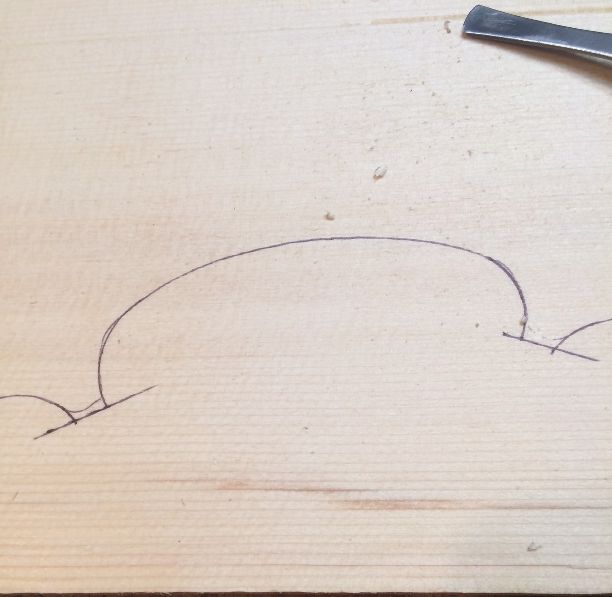

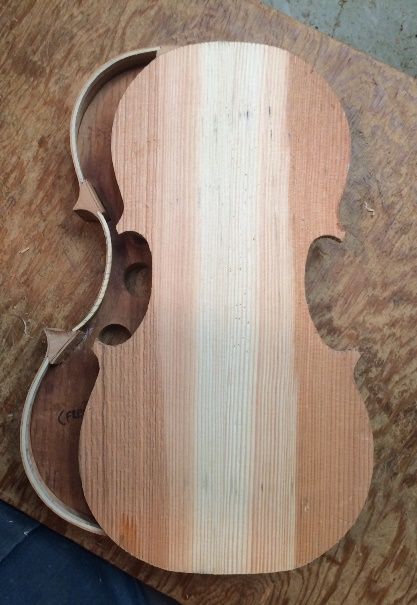

My first book on lutherie was a compilation of a series of blog posts, chronicling the building of a commissioned five-string fiddle. I offered the compliation for years as a free .pdf download, with its companion, “The Journeys of the Swan,” but it did not work well on smart-phones, or other small screens, as the text was just too small to read. So, I have revised and re-formatted the book as an electronic book, and have released it as a Kindle book.

It is only 21,000 words, (which seems short, to me,) but it is profusely illustrated with color photos of the build.

I hope to offer an online series of lutherie lessons later, in keeping with this style

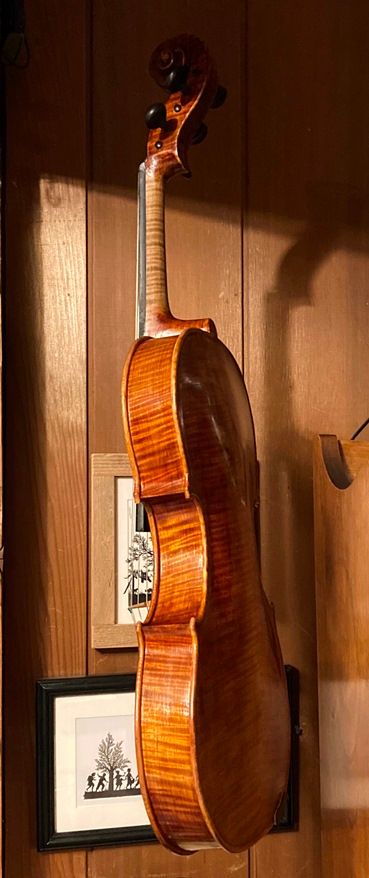

This one is a different kind of story. Kai Jensen, a NASA engineer who loved violins, began to build a cello. However, his health failed him before he could complete his beloved project. Years later, long after his passing, his daughter brought the instrument to me to complete it for him, so that she would have her father’s cello to play.

This is the story, step-by-step, of how we fulfilled Kai Jensen’s dream and it blossomed into a beautiful cello. It is also the story of how his daughter inherited her father’s joy. She named the completed instrument “The Swan,” because the first music sher heard it play was Saint-Saen’s “The Swan.”

These are the Journeys of the Swan.

Booklets

This will probably become a list of articles or short books on resurrecting old fiddles. Only two for now, but more will come. These will appear on Kindle for their minimum price

The Bread Bag Fiddle is a short work (3,800 words, 30 photos) chronicling the transformation of a “junk-store special”…a sadly neglected and abused violin, into the daily player of a gigging fiddler.

“Resurrection of Another Dead Fiddle” is a little shorter, still, but it includes details of internal structural repairs, as well as replacement of missing rib wood and a full neck-set. The customer had sadly set this one aside and bought a cheap violin on which to practice, but after the repairs shown here, this violin returned to being her daily player. She has become a Happy Customer!

.jpg)

.jpg)

![The Bread Bag Fiddle: Resurrecting a "Dead" Violin by [Chet Bishop]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41T5x5WOH7L.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)