Preparing the neck-heel and the neck-block

Measurements for the Neck-set:

There are five measurements to consider in setting a neck on any violin-family instrument:

- Obviously, the distance between the nut and the upper edge of the front plate is a critical measurement. One has to know what is required for the instrument in question and make a mark on each side of the neck heel, as to how deeply it is to be inserted into the neck block.

- The height of the overstand (distance between the top edge of the front plate and the joint between the fingerboard and the neck.) This measurement is taken from the front of the upper edge of the front plate, right beside the neck, vertically, to the top edge of the neck, proper (joint with the fingerboard.)

- The last three are all angles: The plane of the “floor of the neck mortise” must be perpendicular to the centerline of the instrument, and the plane of the bottom end of the neck, proper, must be perpendicular to the centerline of the neck, laterally. If these are both correct, then the fingerboard should project directly along the centerline of the front plate. Any lateral variance from centered is not good.

- The centerline of the neck mortise, from front to back, must be perpendicular to the plane of the plates, laterally, so that it literally “connects” the centerline of the back plate to the centerline of the front plate. Simultaneously, the “footprint” of the neck heel should be bilaterally symmetrical about the centerline of the neck heel. The result should be that the plane of the neck face (when viewed from the scroll) should be parallel with the plane of the plates. (No “twist,” or “roll” in either direction.)

- Finally, the “Projection angle” should be such that the height of the “projected fingerboard angle” should be at the appropriate height for the instrument in question at the bridge line. (This can either be literally measured as a projection height at the bridge line, or, if you know how high the end of the fingerboard will be if all other factors are correct, you can simply measure it there. The danger in this is that if the other measurements are not quite right, and you simply measure the height of the end of the fingerboard, then the projection angle will be wrong, and you will not discover it until it is too late to correct it. (Ask me how I know!)

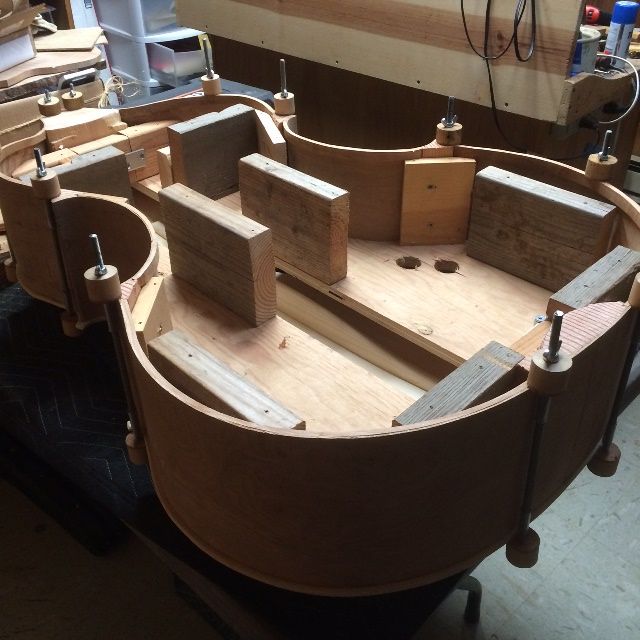

Planning the Neck-Set

In the case of a bass, with a removable neck, as well as all the other enormities of a double bass (as opposed to the smaller instruments) I had to not only consider the five measurements listed above, but consider how to achieve those angles reliably when removing and reinstalling the neck repeatedly. It all has to come together correctly without the customer having to “measure” anything, except to correctly carry out the assembly and minimal set-up.

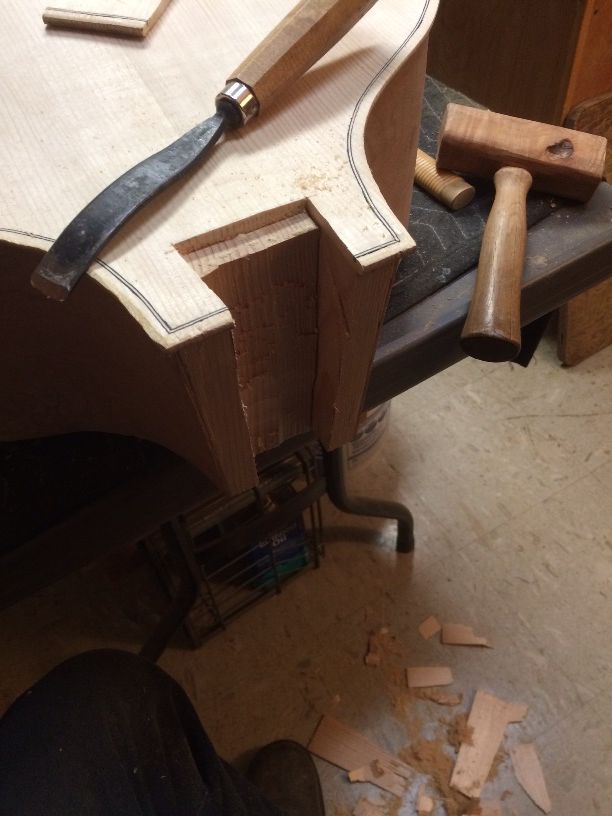

Cutting the Neck-mortise

I had already cut the “footprint” of the neck-heel, so I took measurements and laid out the proper shape on the end of the neck-block, where the mortise was to be cut. I worked from the centerline of the neck block, so there was less chance of ending up with a skewed neck.

Then I turned the corpus over and began sawing the sides of the mortise, using a thin-bladed Japanese pull-saw:

Once I had the two sides sawed out, I sawed across the line between the two sides and separated the rectangle of the front plate wood from the neck block, to expose the neck block, allowing me to use chisels for most of the remaining removal of wood from the neck-mortise.

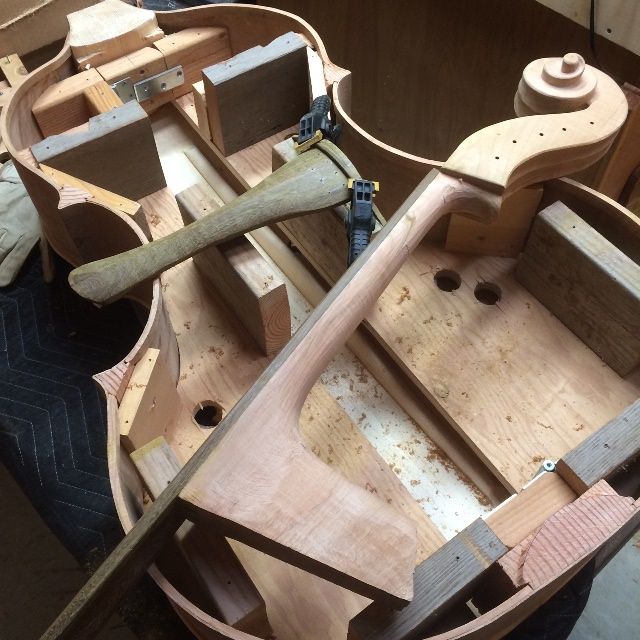

I checked the fit continually until all five measurements were correct, then removed the neck from the mortise, and began fabricating the “removable neck” apparatus that will enable the player to pack up his or her bass and transport it safely.

One of the things that concerned me was the possibility of wood changing shape through wear or stress. And, since the neck is to be secured by a bolt, how can I be sure that the bolt will not gradually wear into the wood, causing a loose fit?

After fitting the neck to the corpus, as outlined above, I inlaid 1/16″ Carbon Fiber plate on both sides of the neck heel, to provide smooth, stable fit every time and simultaneously guard against a heel crack, as the CF plate is not only inlaid into the sides of the neck, but it is bedded in epoxy, so it is a permanent part of the neck heel, providing support as well as a smooth surface to the sides.

I used screws and epoxy to mount bars of CF across the ends of the “joint” between the neck heel and the portion of the neck heel that will be permanently mounted to the corpus (and secured to the block and button,) so that a bar of CF on the neck heel slides under a similar bar in the mortise, thus providing an anchor of sorts.

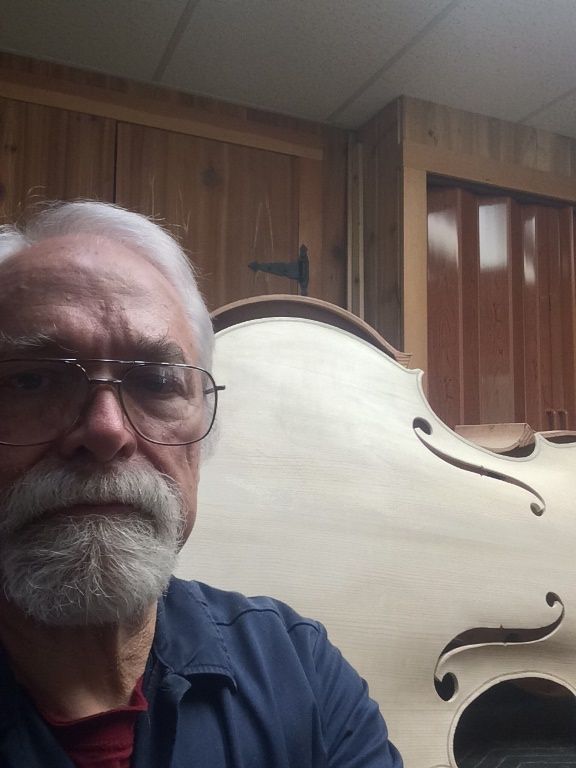

Then I re-attached the two portions of the neck heel using a piece of paper glued between them, so that I could check the neck-set one last time, before gluing the root end in place and drilling the removable portion to receive the bolt. The paper provides a “breakaway joint” that will be relatively easy to separate after the heel root is glued home. it is only glued with a few “stripes of glue on each face, so the paper will tear apart and allow me to extract the removable portion the neck and finally complete the drilling, installation of a threaded insert, etc., and thus complete the neck set.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

_2.JPG)