The Call

A couple of months ago, I received a phone call. I glanced at the “caller-ID” thing, and I thought, “I don’t know anyone in Ohio: this is probably spam!” But I cautiously answered, and was surprised to hear: “Um, hi! Yes, I was interested in a five-string fiddle…” (I instantly changed gears, mentally, and shifted from “Is this another spam-call?” mode, into “Yes! How can I help you?” mode!)

Turned out he specifically wanted a handmade, luthier-made acoustic five-string violin. I had a couple in stock, but he looked at the pictures and asked, “What else have you got?”

(Hmmm! Now what?)

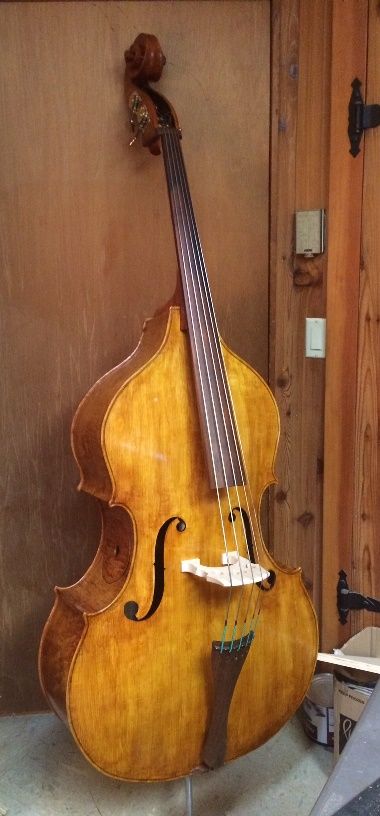

“Well, I have one that I had begun, using scrap from the five-string double bass I just completed….” So I sent him pictures of the beginnings of an instrument:

There wasn’t a great deal to see, but he liked it and asked how long it would take to complete it. I guessed “at least a month,” and he said, “Fine! Send me pictures as it progresses!” And that was that!

Progress Reports

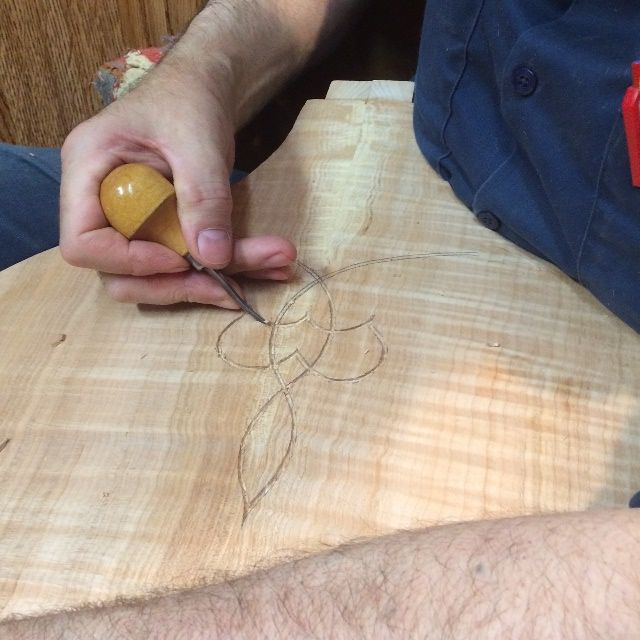

So I sent photos and progress reports, and he asked questions. We chatted via e-mail and phone chat messages, during that month, during which he saw things like:

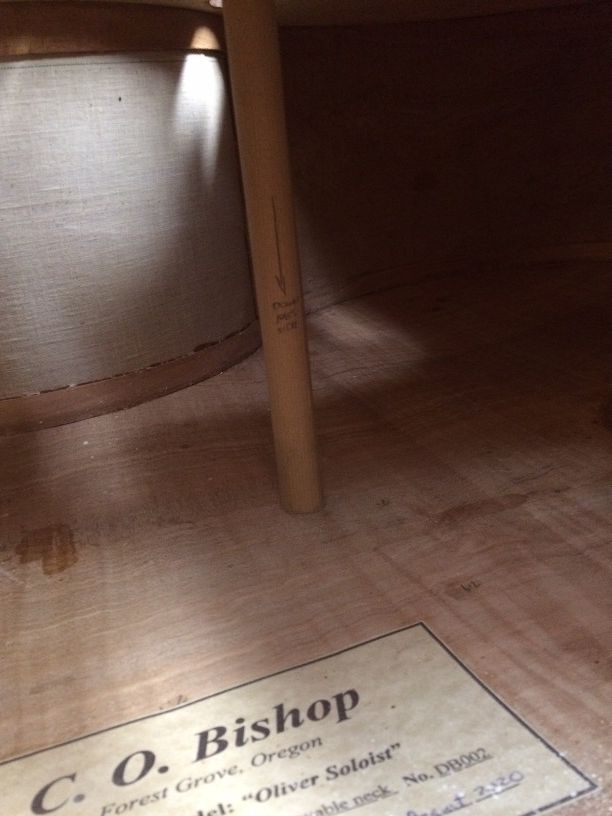

He was especially encouraged to see proof that I actually build my instruments from the raw wood. He had already discovered that there are makers who put their label on other people’s factory-made instruments and claim they made them. (If someone can’t afford a handmade instrument, I will offer the option to buy one purchased in the white, and finished in my shop, but I never put my personal label in such an instrument: I did not build it! My own work is all signed and numbered.)

And finally, the set-up instrument:

The Visit and Delivery

He was growing more and more attached to “his” instrument as it progressed, so, as it neared completion, he made plans to fly here to Oregon (with his family) to be the first to play it! This is what he encountered when he and his family arrived:

He brought his wife and two sons with him, and they patiently waited (From about 1 PM to 10 PM!) while he played ten of my violins, three of my violas, and, of course, the “prize five-string!” (I still have “Orange Blossom Special” racing through my head, today!) This is how the living room looked when they left! 🙂

He ultimately bought the five-string fiddle, packed it into a hard-shell case, and then he and his family headed off to the Pacific coast (the next morning) to hike around the Cannon Beach area, as well as Ecola State Park.

They found a little shop in Cannon Beach where he bought a stand for his new fiddle:

And then they flew home to Ohio! But He graciously took time to write a review, and allowed me to post it here, including his name!

Andy Pastor Review

I’m leaving this message of gratitude to Chet Bishop and his family for others to see and hopefully help them make a decision to purchase one of his fine instruments.

I purchased a five-string violin which he had just begun carving months ago and which became a commission violin for me. I flew from Ohio to his beautiful place in Oregon where I had the pleasure to meet Chet, his wife Ann, and his son Brian Bishop. By the way, Brian is a premier guitar luthier who had several guitars with him as well as guitars in local well-known music stores. His guitars sound better than any Martin, Taylor, or Gibson I have heard (attention to detail and work performed inside the body of his guitars sets them apart).

There is so much to say about a Chet Bishop violin and the experience, so I’ll make it bullet points:

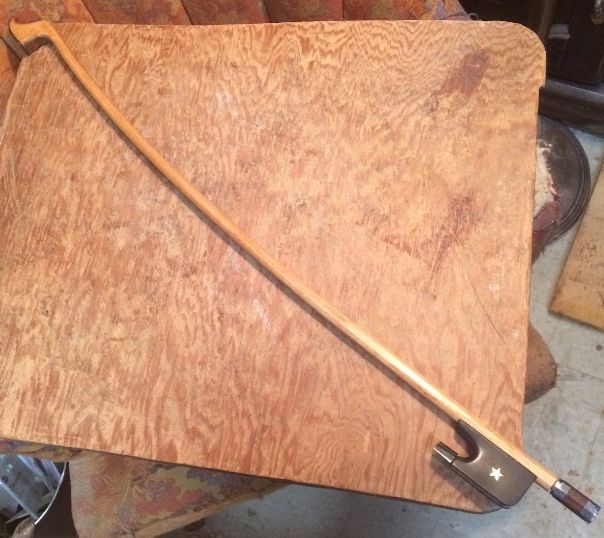

- The sound of a Chet Bishop violin is perfectly balanced on all strings. This is not easy to get a deep clear tone from a C string on an acoustic violin, but this is his specialty. No issue getting that rich sound out of the C string with my lighter weight carbon fiber Coda Bow Diamond GX or my Franz Winkler Pernambuco bow. No need for a heavy bow to get the C to ring!

- The violin is handmade (not a kit) and he knows exactly where the wood used is from. He has specific wood he uses ( and showed me his supply) which I feel gives each violin its own unique and beautiful sound and, of course, look. The quality of the build process is fully under Chet’s control. (Unfortunately, there are more than a few violin makers using pre-made “white” violin kits and selling them as hand-made. Be aware and do your investigation!)

- The feel of the five-string Chet Bishop made violin is so similar to a four-string, it makes transitioning between a four and five-string violin easy. The string spacing and bridge/fingerboard arching are dialed-in, and his years of violin making are apparent.

- The finish of my violin as well as all the other Chet Bishop violins that I had the pleasure to try is similar to the old Master violins from Italy. Cheap student violins all have that high glossed finish look, it’s hard to see the grain on the top of these foreign-made violins, and even harder to feel the ever-so-slight structure of the grain. Probably why these factory violins made in low-cost countries all sound the same; no real soul.

- Attention to detail can be noticed at first glance, even by any non-musician. The unique purfling design on the back, the internal strengthening (used by the old master builders to make their instruments last hundreds of years), small unique features of the saddle and nut, the wood sealing and varnish process, cycloid arching of the back plate, just to list a few, all add to the quality and beauty. This detail will certainly allow the violin to actually improve over time (not that it needs to!!).

- Then there is the experience of watching the violin get made. Chet provided daily progress photos and explanations, we communicated via text and sometimes email. This was very exciting. I know more about how a violin is made than I ever thought possible, at least without going to a violin-making school. I also got to know the luthier during this process, such a bonus to know your violin maker. He understood what music I played (in a band environment) and kept that in mind during the build process. (Although any of his violins could easily be (and are) top performers in any style: classical, jazz, country, bluegrass, spiritual, klezmer, Irish, Celtic….)

- The benefit of visiting the violin maker and trying out the instrument cannot be overstated. Chet and his wife are extremely inviting people, as he said, “ordinary folk.” I probably tried out over 10 of his violins and violas, this was a real pleasure to hear each instrument and compare sounds to the five-string I purchased. Chet and his wife are so patient: I spent a full day with them (10hours). We did some minor adjustments to the five-string violin after I had played it: changed the chin rest, changed the e string, lowered the bridge a very slight amount, and a tiny soundpost move. He made sure everything felt perfect before I left. His wife made us some fantastic burritos for dinner, hot apple cider, and apple scones for snacks/dessert! As I said, very welcoming people, we had great conversation: Chet is extremely knowledgeable and I’m so grateful he shared some of this knowledge that day. Although these are truly the benefits of a visit, he has no issue shipping a violin, and I feel these minor adjustments could be handled remotely and/or by myself.

- I’m including this last bullet point because… how many people can say they have a Sequoia tree on their property? He has at least two! (I got photos by both.) Chet is a wealth of knowledge about the area, I’m so thankful he suggested visiting Cannon Beach / Haystack Rock / Ecola State Park on the Pacific Ocean. This added to making the trip even more memorable. Even saw a herd of wild elk grazing just feet from me at one of the scenic views.

I hope this review not only expresses my gratitude to Chet Bishop and his family, but also provides assurance and guidance for anyone considering one of his fine instruments. He makes the whole violin-family of stringed instruments and his son, Brian Bishop, covers the family of guitars. Looking forward to another visit in the future. Truly an heirloom instrument!

Thank you, Chet!

Andy Pastor,

From Ohio

Here is one of the “baby” Sequoias which Andy liked so much: My mother planted them 50+ years ago. 🙂 They are only 5 or 6′ in diameter.

Thanks for the very kind review, Andy!

And to all my readers,

Thanks for looking!

🙂

🙂

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)