Side Access port and Neck set

Neck Connection

One of the problems with creating a double bass whose neck is removable for traveling is that there has to be a way to connect and disconnect the neck. Thus you have a choice– will the fasteners be visible from the outside, or hidden inside?

I have seen several examples of both, and I really prefer the hidden fasteners approach. BUT! That also mandates that there be a way to access the interior to tighten or loosen the fasteners. I have chosen a 3/8″ diameter bolt (tensile strength exceeding 5,000 pounds) and a large flat washer embedded in Epoxy on the inside of the neck block. The bolt extends through the washer and the neck-block and engages the threaded insert in the maple wood of the neck heel (see below.) So…the next step is to consider a side-access port through one of the C-bout ribs,

Access port

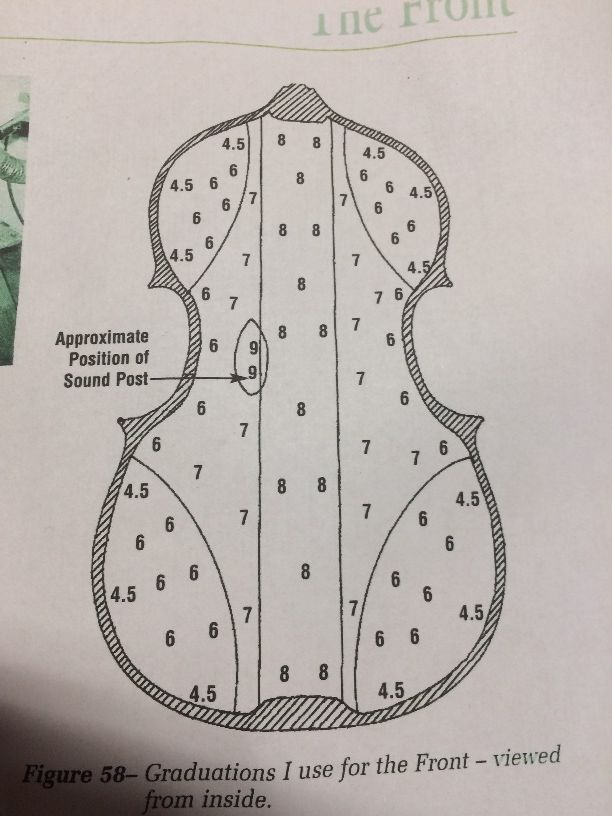

I chose to make the access port through the bass-side c-bout rib: the player will reach up through the port with his or her right arm to access the single bolt in the neck-block. As an added bonus, the soundpost is also easily accessible, as it will surely need to be re-positioned after having the bass apart for travel. (In fact, it is so nearly guaranteed to be loose, that I intend to provide a pocket in the instrument case for the soundpost, as well as the bridge, the tailpiece, and the neck assembly, etc. That way there is no question: as you reassemble the neck, you will also re-set the soundpost, after the strings are on, but before it is up to tension.) Finally, as another luthier pointed out, if there is ever repair-work to be carried out inside the bass, this access port makes it a much simpler task, thus saving money and time.

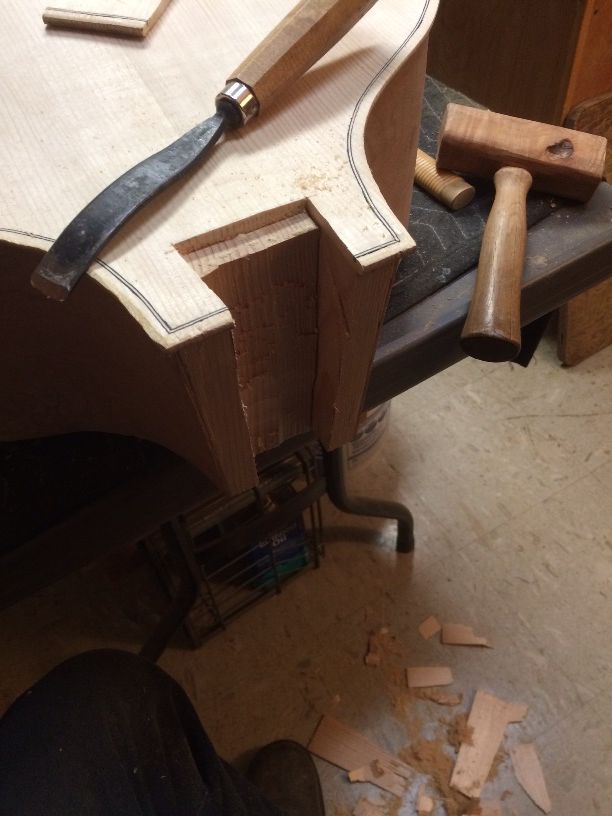

So: how to carry out the access port plan? I positioned the proposed hole on the bass-side c-bout rib, roughly centered, and laid out a 5-3/4″ circle. I cut out the circle using an X-acto knife, then smoothed the cut edges with a file and sandpaper. I wanted to use that piece for the closure, as well, so I couldn’t afford any damage to either the rib or the cover plate.

Initially, I had thought I would employ a drawer-pull-type handle as a means to open and close the access port, but I didn’t care for the looks, so, after further reflection, I chose to make a simple “finger-hole,” instead. I reinforced the single-thickness of rib-stock with two more, especially near the center, so that the rib would be stronger, and so that the edge of the rib where the finger contacts it will be 6mm thick instead of 2 mm, thus much more comfortable.

I reinforced the actual c-bout rib by adding a second thickness of ribstock to the entire inside of the existing rib, and I cut a slightly smaller hole in it so that the closure plate had a shelf to rest against. Also, this is the surface into which the neodymium magnets will be inset, to hold the closure plate in place.

(I realize that the above photo looks a little as if there were a plexiglass cover on the hole, but those are not reflections: you are looking through the hole at some pads behind the bass body. I was using the pads to protect the front plate, earlier.)

I added the reinforcement to the cover plate and sanded the interior of the finger-hole to be very smooth.

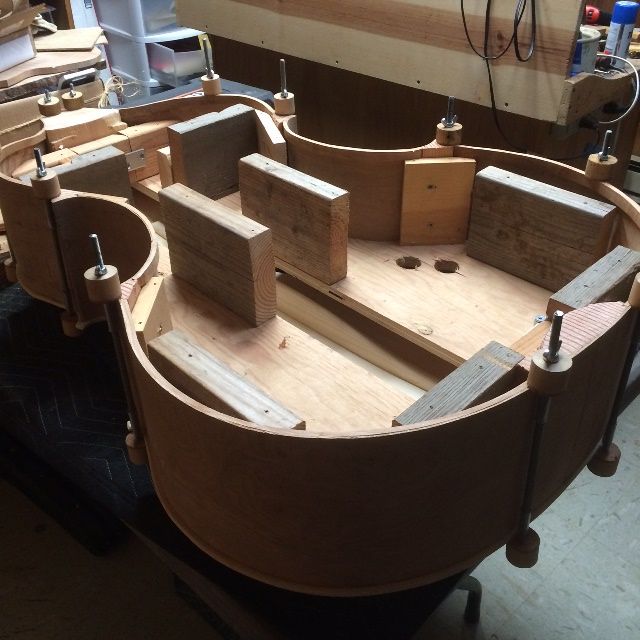

Cleaning up the interior

While the glue was drying on all the above assemblies, I took the time to complete the shaping of the blocks and linings, so as to be ready to close the corpus, once all the interior work is done.

I used a knife a gouge and a small plane to shape the linings and blocks. Then I used a scraper to ensure that it all was acceptably smooth.

Neck Set

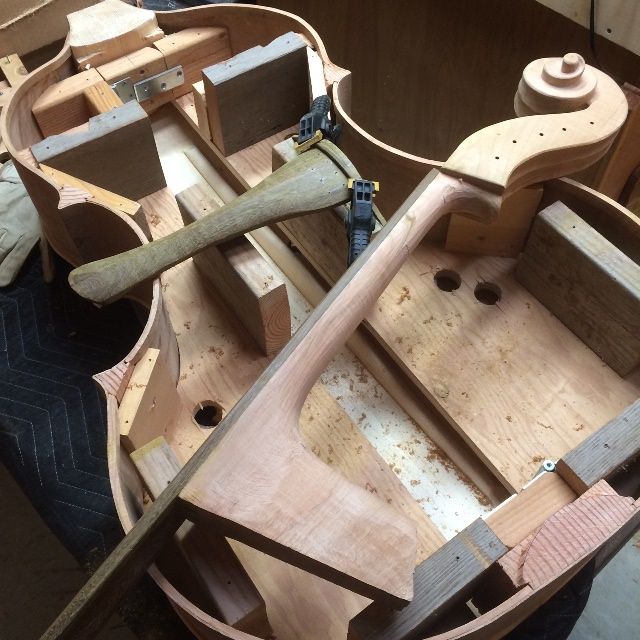

I had checked and re-checked the fit of the neck-heel into the mortise in the neck-block, until all the measurements were correct, and then I had drilled a pilot hole through the neck-block into the neck heel. That established the position and range of both holes, so that when I drill for the insert and r-drill for the bolt, the holes will still be in line with one another. I bedded the large plate washer in epoxy on the inside of the Sitka spruce neck-block, so that the bolt would not be able to gradually wear a hole deeper into the soft spruce.

With the neck temporarily in place, I could check to see how much of the excess neck-heel “root” would have to be sawn off and planed flat. You can see, also, that I had glued the heel-block “root” onto the neck-heel proper, using a sheet of paper between them as a “breakaway” layer, so that when everything was correct, I could easily pop the neck free from the root.

As it turned out, hot hide glue does not bond well to carbon-fiber plate. So, after I discovered that the neck-root was actually not glued home, I was forced to choose epoxy as a final bond for the portion of the neck that is intended to remain permanently in the neck mortise. I don’t like doing this, as epoxy is not reversible, but there was no viable option. After making that choice, though, I took a sharpie pen, and wrote, inside the mortise, a notice to any later repairers, that those three joints (bottom and both sides) at the neck root are epoxy. (Sorry)

But I can put the neck on and take it off and put it on again, and it fits correctly, and all the measurements have remained correct.

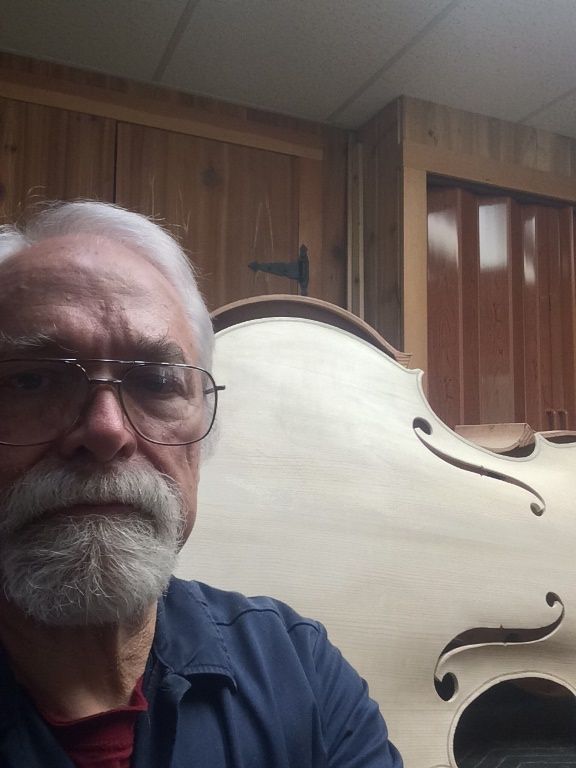

And it is looking pretty good:

Next time we will talk about the final work before closing.

Thanks for looking.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)