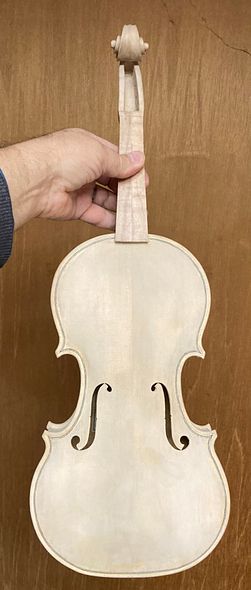

Starting With Bare Wood

Last time, I gave a preview of some of the varnish procedure.

But, to be more specific, let’s walk through the varnishing process:

Peparing for Varnish

First, I removed the fingerboard to give me access to every square milimeter of the outside of the instrument. Next, I used low-angle light, to cast dark shadows so that I could see all the discontinuities, humps and hollows. Then, I gently scraped all the surfaces to remove all of those discontinuities.

Finally, I was ready for the varnish procedure:

Mineral Ground to Close the Pores

To begin with, I used a suspension of fine particles of gypsum in either water or coffee, to form a mineral ground. First, I brushed the mixture onto all the outside surface except the handle area of the neck, Then, using my fingers, I rubbed the mixture into the wood, so as to fill the natural pores wtih “nano-particles” of the gypsum.

After the mixture dries, the instrument looks chalk-white, and the mineral ground obscures the wood grain.

Then, I used 400-grit sandpaper to very lightly rub off any excess dry gypsum, which still left the violin looking stark-white, as the gypsum had filled the pores of the wood.

Obviously, that (mineral ground) stage of the process looks pretty awful. but the next step (sealer application) always feels like “magic” to me. The sealer makes the mineral ground permanently “disappear!”

Sealer

For the last ten years, or so. I have used a sealer which is simply a thin solution of rosin in alcohol. Sometimes, I use turpentine instead of (or in addition to) the alcohol. Either way, the solvent carries the rosin into the pores, surrounding the particles of gypsum, and thereby rendering the particles tranparent. (However, on this fiddle, I chose to use alcohol as the solvent.)

Obviously, the mineral ground has done its work, plugging the pores against penetration by varnish. However, it has also become permanently invisible.

NOW we Varnish!

When I began making violins, I was using oil varnishes. Later, I switched to spirit varnishes. Today, I am still using a spirit varnish.

The main chemical difference between the two is that an oil varnish is composed of a mixture of a drying oil and a resin of some kind. The varnish-maker cooked the oil and resins together at a high heat, thereby forming a polymer, which is no longer either oil or resin. It does not dry by evaporation so much as by a continuation of the poymerization process, and by “off-gassing” the volatile portions left in the mix.

Varnish makers prepare the spirit varnishes, on the other hand, by dissolving one or more resins in a solvent. Incidentally, the solvent is usually, (but not always) alcohol. When the solvent evarporates, the resin (or resins) remain(s) in and on the wood, to finish hardening. (The mineral ground helps to prevent deep penetration of the varnish into the wood. This is desireable because the varnish-saturated wood does not vibrate the same in comparison to the unsaturated wood, and it can thereby dampen the sound.)

I always begin with a yellow varnish, so that the yellow base coats will “shine through” any thin areas of the darker vanish, providing a reflective “glow” from within.

Yellow Varnish Base Coats

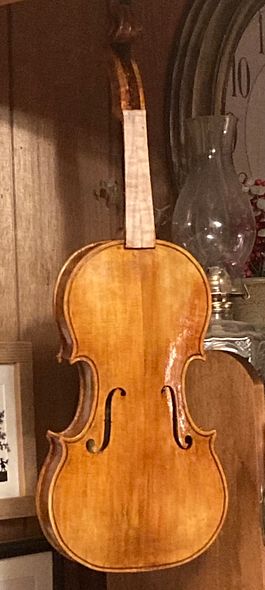

Here is the fiddle with two coats of yellow varnish:

The grain begins to become more visible with thje addition of the varnish. There is a temptation to stop early, because the grain becomes highly visible after about three or four coats of varnish. But it will look better with more.

Building the Color

I began deepenind the color by simply adding a thin coat of brown varnish, over the yellow base coats.

I loved this look…it seemed as though the Quilted Maple wood was in flames, or perhaps as if I was seeing an incredibly dramatic sunset in progress. But I knew it needed more.

Shading

Obviously, (as you can see) I am applying more color in certain areas. I am attempting, thereby, to give the impression of truly aged varnish (where the colored varnish has ben worn away in certain areas through much use.) Some people don’t like that look, but many do. Most importantly, I like it. Charles Beare was famously quoted as having said, “There is absolutely no reason to ‘antique’ or ‘shade’ a new instrument...unless you actually hope to sell it!” (Apparently I’m in good company!)

So, I apply more varnish in the areas where hands would be least likely to touch, and where the surface is least likely to be abraded by any means. But, I try to be gentle about this, not heavy-handed. Some (few) makers deliberately damage the wood, in an effort to imitate advanced age. Their instruments sell to people who like that look, but I don’t want to do that. Therefore. I simply brush on deeper color in the areas of least wear.

Usually, I prefer instruments to be at least a little leaning toward a red-brown color, so, I needed to add some red.

More Color

I brushed on a thin coat of red-brown varnish all over:

But it still needed more! Consequently, I added more brown in the corners, and allowed it to dry. Then I added more red.

Finally, the varnish reached a depth of color about which I felt pretty good!

Then, I french-polished the instrument, to flatten any brush-marks. Now I will allow it to dry and harden for a couple of weeks before I set it up for playing. Otherwise, it will acquire deep fingerprints as I work on it.

Thanks for looking!